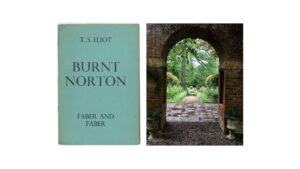

T. S. Eliot himself pointed out the close relationship between the Four Quartets and the four elements. Burnt Norton and its sudden shaft of sunlight is the poem of air; East Coker reminds us that life comes from and returns to earth; the dominant symbol of Little Gidding is fire. The element of The Dry Salvages is unquestionably water, in the form of river and sea.

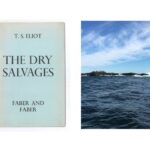

The Dry Salvages are a group of rocks off the coast of Massachusetts, the only American location in this transatlantic sequence of poems. The rocks lie a couple of miles from Rockport, close to Gloucester, where the Eliot family had a holiday home. Though he grew up in Missouri, the young Tom Eliot spent every summer of his childhood in New England.

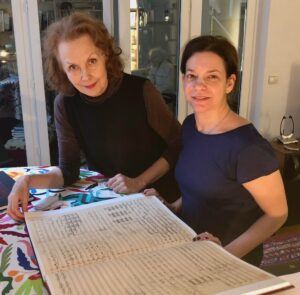

The Eliots’ house in Gloucester is now a writer’s retreat, owned and managed by the T. S. Eliot Foundation and it was there that Pam and I spent a night before visiting the Dry Salvages.

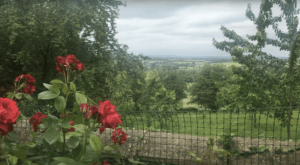

The house is spacious and welcoming. In Eliot’s day, its porch had an uninterrupted view of Gloucester Harbor, though trees have now grown up around it. It was an extraordinary feeling to stay there, in the rooms where T. S. Eliot slept and lived as a boy, in that landscape that he loved so much.

We had arranged for a local fisherman to take us out to the rocks on the afternoon we arrived in Gloucester, but the sea was too rough to get to the Salvages comfortably, so our journey was postponed till the next day. Instead we went for a walk out to Eastern Point. Here, next to the lighthouse, we came across a large bell. The sign on it read: ‘This bell was used as the fog signal at Eastern Point Light House from June 1933 to Dec 1969. Cast in Chelsea, MA. Gold dust was sprinkled on the mold in order to obtain the right tone.’

Eliot wrote about just such a bell in The Dry Salvages:

And under the oppression of the silent fog

The tolling bell

Measures time not our time, rung by the unhurried

Ground swell, a time

Older than the time of chronometers..

The bell is an essential sound of the sea for Eliot – and by now it had become eerily apparent that bells were also accompanying us throughout our Four Quartets pilgrimage: the bell on the house at Burnt Norton, in the churchyard at East Coker and now here, on the promontory where Eliot played as a boy. Would there be a bell at Little Gidding too?

The next morning dawned warm and bright and the sea was entirely calm as we drove to Rockport to meet Captain Bill Lee, who would take us out to the Salvages. Bill has fished the waters off Cape Ann all his life. We asked him whether many tourists asked to be taken round the rocks; no, he said, in all these years only one other person had made the trip with him – an Englishman. We later realized that this was the actor Jeremy Irons, a great devotee of Four Quartets.

Photo by Gideon Lester

It took about an hour to journey out to the Salvages. The rocks are low-slung – just a metre or two above sea level and the cluster is almost entirely covered at high tide, making it hazardous to shipping. Even on this calm day there was a significant swell and except for a large colony of seals, there was little sign of life in this barren, remote place.

As we steered around the Salvages and headed back for the domestic familiarity of Rockport we thought of Eliot’s description of the ‘ragged rock in the restless waters’:

Waves wash over it, fogs conceal it;

On a halcyon day it is merely a monument,

In navigable weather it is always a seamark

To lay a course by: but in the sombre season

Or the sudden fury, is what it always was.