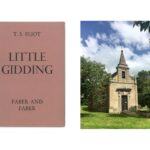

The final stop on our Four Quartets pilgrimage was Little Gidding, a tiny hamlet about 30 miles northwest of Cambridge. An Anglican religious community was founded there in 1626 by Nicholas Ferrar, a friend of the poet George Herbert. It came under attack during the English Civil War and briefly served as a refuge for King Charles I when he was fleeing Cromwell’s troops.

Eliot probably only visited Little Gidding once, in 1936, but it impressed him sufficiently that he named the final quartet after it. He wrote it during the Blitz, in 1941, while serving as a volunteer fire watcher. The poem is full of references to wartime and death (the ‘dark dove with the flickering tongue’ is a German fighter bomber) and it seems likely that Eliot was thinking of the remote village’s role as a place of sanctuary in a historical war when he chose it as the final location for Four Quartets.

As with Burnt Norton and East Coker, Eliot guides us towards Little Gidding with a detailed description of place:

If you came this way,

Taking the route you would be likely to take

From the place you would be likely to come from,

If you came this way in may time, you would find the hedges

White again, in May, with voluptuary sweetness.

It would be the same at the end of the journey,

If you came at night like a broken king,

If you came by day not knowing what you came for,

It would be the same, when you leave the rough road

And turn behind the pig-sty to the dull facade

And the tombstone.

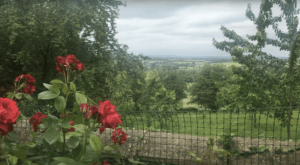

We made our journey in May and sure enough the hedges were white with spring blossom. As we drove towards Little Gidding, we marvelled at how specific Eliot’s directions were. The hamlet is in the middle of fields and there is really only one way to reach it. The final stretch of road is a dirt track and then, sure enough, it turns behind some farm buildings and an old brick pigsty.

Our guide was Judith Hodgson, who, together with her late husband Tony, had run a new religious community at Little Gidding from 1970 until 1998. Judith is now a docent at the visitor’s centre and couldn’t have been kinder or more welcoming. She gave us tea and cakes and then left us to walk on to the chapel with its ‘dull facade / And the tombstone.’

The Church of St Mary is tiny and entirely surrounded by fields. We were pleased and not at all surprised to discover our fourth bell, set in the door above the entrance door. Inside there is space for perhaps thirty congregants, all facing each other, while on a wall hangs a sampler embroidered with words from Eliot’s poem.

Once again we were walking in Eliot’s footsteps; once again we imagined him here in the still, prayerful place, both when he visited in person and when he journeyed back to Little Gidding in his imagination during the horror of the Blitz.

All photos by Gideon Lester

Outside, the trees were covered in blossom and the still spring air was broken only by birdsong and the distant bleating of sheep. We sat under a yew tree, close to a bed of yellow roses and the tombstone by the western door and read Eliot’s poem:

The moment of the rose and the moment of the yew-tree

Are of equal duration. A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. So, while the light fails

On a winter’s afternoon, in a secluded chapel

History is now and England.

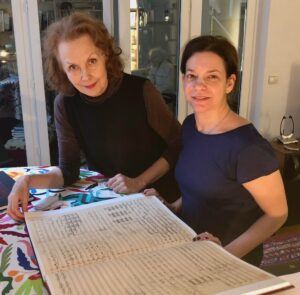

Our physical journey was over. Now a new journey began, as Pam began to imagine how our visit to these four quiet, out-of-the-way places would find new embodiment in the dance that she would soon start creating for Four Quartets.