“The differences between a great dancer and a merely competent dancer is in the vital flame, that impersonal, and, if you like, inhuman force which transpires between each of the great dancer’s movements.” (T. S. Eliot, “Four Elizabethan Dramatists”)

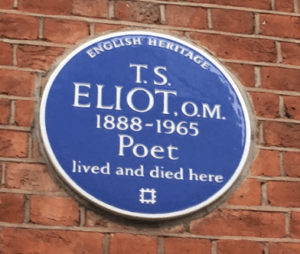

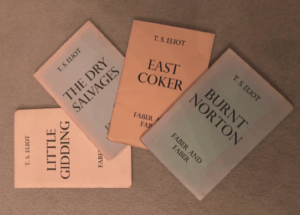

In his poetry, T. S. Eliot strove to create a kind of abstraction that he referred to as “depersonalization.” He also saw this quality reflected in dance and music. The critic Edwin Muir, in reviewing Four Quartets, likened the poems to Beethoven’s late string quartets, noting “they certainly resemble the quartets in this combination of remoteness and intimacy, a strange but harmonious combination. They are remote because they pass beyond time as we ordinarily conceive it, and intimate because they go to the hidden heart of human experience and touch ‘the still point where the dance is.’”

In a letter to the Bloomsbury author Mary Hutchinson, Eliot wrote: “I like to feel that a writer is perfectly cool and detached, regarding other people’s feelings or his own, like a God who has got beyond them; or a person who has dived very deep and comes up holding firmly some hitherto unseen submarine creature. But this sort of cold detachment is so very rare…” Eliot loved dance in part because it allows artists to express this kind of abstraction, complexity, and ambiguity that he sought in his own writing – “that impersonal, and, if you like, inhuman force.”

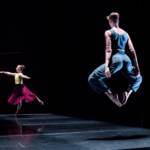

I’ve recently spent time in rehearsals with Pam Tanowitz as she creates the choreography for Four Quartets, and have been struck by how much the vital flame that Eliot described is present in her dances. I find her performances deeply moving, in part because they exemplify the “combination of remoteness and intimacy” that is also in Eliot’s poetry.

Look, for example, at this recording of Pam’s 2016 dance the story progresses as if in a dream of glittering surfaces. Fragments of narratives seem to arise and dissolve; the dancers’ bodies seem to create relationships with each other, and then suddenly appear isolated. They tell stories, and then they don’t. As Muir writes of Eliot, Pam’s dances “are remote because they pass beyond time as we ordinarily conceive it, and intimate because they go to the hidden heart of human experience.”

Pam Tanowitz’s the story progresses as if in a dream of glittering surfaces

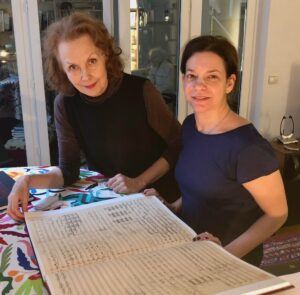

This paradoxical conversation between the depersonalized and the personal is a defining feature of Pam’s choreography. It is why, I think, she is such a good match for Eliot — along with her other collaborators on the project, Kaija Saariaho, and Brice Marden, who are both abstract artists with a deep sense of humanity. It also explains her deep affinity for Bach, whose Goldberg Variations she recently set to dance, to great acclaim. (There’s a beautiful documentary about Pam’s New Work for Goldberg Variations online here.)

Pam is an entirely contemporary choreographer, who is also deeply aware of her lineage. Her dances are infused with references to ballet and the modern and post-modern choreography of Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Trisha Brown, and others. Her deep knowledge of the past creates another parallel with Eliot, who famously stated in his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” that all great artists create work in constant dialogue with the past as well as the present. “This historical sense, which is a sense of the timeless as well as of the temporal and of the timeless and of the temporal together, is what makes a writer traditional,” he wrote. And it is at the same time what makes a writer most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his contemporaneity.”