The music for our Four Quartets is by the esteemed Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho. We approached her about the project because we knew that she loved Eliot; one of her earliest works, “Study for Life”, was inspired by Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men”, and on the last page of the score of her cello concerto “Notes on Light” she included a quotation from “The Waste Land.” We were beyond thrilled when she accepted our invitation to create a musical score to complement the poetry of Four Quartets.

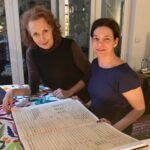

Kaija Saariaho and Pam Tanowitz in Kaija’s Paris apartment. Photo by Gideon Lester

Kaija is one of the world’s leading contemporary composers. Last year she became the second woman ever to have an opera produced at the Met (the first, appallingly, was in 1903.) Her shimmering compositions combine elements of minimalism and “spectral” electronic music with melodic writing for chamber groups, orchestras, and the human voice. For Four Quartets she has created a score from several pieces for solo and ensemble strings and electronica. If you’d like to listen to them in advance of the performance, they are:

- “Fall” for harp and electronics

- “de la Terre” for violin and electronics

- “Cloud Trio” for string trio

- “Spins and Spells” for solo cello

- “Vent Nocturne” for viola and electronics

Kaija’s music combines remarkably well with the poems of Four Quartets – in part, I think, because of the spacious, open structure of her compositions, and because there is already such a deep musicality to Eliot’s writing. Eliot had long experimented with musicality in his poetry (think of that famous approximation of jazz rhythms from The Waste Land – “O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag— / It’s so elegant / So intelligent”) but it was in Four Quartets that his equation of words and music reached fullest expression.

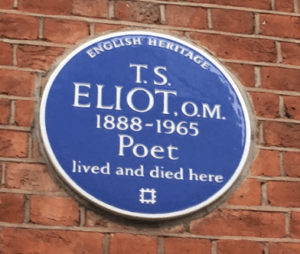

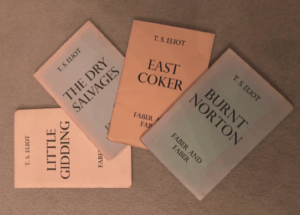

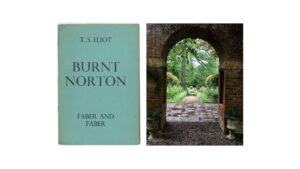

Even the title Four Quartets suggests a self-conscious relationship with the structures of chamber music. Eliot elsewhere noted: “I am also interested (Burnt Norton) in possible approximations to musical form and musical effect.” In a letter to his editor John Hayward in 1942, Eliot addressed the musical connotations of “quartets”:

“I am aware of general objections to these usual musical analogies: there was a period when people were writing long poems and calling them, with no excuse, ‘symphonies’ […] But I should like to indicate that these poems are all in a particular set form which I have elaborated, and the word ‘quartet’ does seem to me to start people on the right tack for understanding them (‘sonata’ in any case is too musical). It suggests to me the notion of making a poem by weaving in together three or four superficially unrelated themes: the ‘poem’ being the degree of success in making a new whole out of them.”

The form of Four Quartets is profoundly musical. Each of the four poems is built around the same five-part structure, which unites short lyrics and longer discursive and philosophical sections. Much of the power of Four Quartets lies in intricate metrical shifts that call to mind Eliot’s love of Beethoven’s late string quartets, which Eliot discussed in a letter to the poet Stephen Spender in 1931, five years before the publication of Burnt Norton. Eliot wrote to Spender: “There is a sort of heavenly or at least more than human gaiety about some of his later things which one imagines might come to oneself as the fruit of reconciliation and relief after immense suffering; I should like to get something of that into verse once before I die.”

Music also provides a central thematic thread in the poems; like dance, it becomes a way for Eliot to approach the most profound human experiences which can’t fully be captured in words. In The Dry Salvages he writes of “music heard so deeply / That it is not heard at all, but you are the music / While the music lasts.” The magnificent final section of Burnt Norton ends with a reflection on the power of music to express the transcendent aspects of our lives:

Words move, music moves

Only in time; but that which is only living

Can only die. Words, after speech, reach

Into the silence. Only by the form, the pattern,

Can words or music reach

The stillness, as a Chinese jar still

Moves perpetually in its stillness.

Not the stillness of the violin, while the note lasts,

Not that only, but the co-existence,

Or say that the end precedes the beginning,

And the end and the beginning were always there

Before the beginning and after the end.

And all is always now.

Whenever I hear the haunting sonorities of Kaija’s compositions, I am reminded of Eliot’s description of music that “Moves perpetually in its stillness.” It was as if these words and music were made to complement each other.

• • •

There are very few actual settings of Eliot’s poetry as songs, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats notwithstanding. After Eliot’s death, his widow Valerie, who created the terms of his estate, was clear that her late husband’s major works were not to be sung. Exceptions have been made only twice – for Elliott Carter’s “Three Explorations,” based on stanzas from Four Quartets, and Stravinsky’s gorgeous motet “The Dove Descending,” which sets a lyric from “Little Gidding.” Eliot and Stravinsky were close friends, and Stravinsky composed the anthem in 1962.